Threat Actors use Slack for C2

Threat actors used Slack — an IRC style chatting system comprised of workspaces and channels — and GitHub to gather information in a targeted attack. Trend Micro originally reported on the SLUB backdoor, which utilized a compromised website to deliver the loader, back in March. That watering hole attack campaign started at the end of February and appears to have ended by the time the Trend Micro analysis was published. The use of third-party services to issue commands, receive output, and exfiltrate data made it difficult to track these actors, and the lack of operator-owned infrastructure resulted in the threat actors not being identified. However, some information indicates that both the targets and the attackers are centered on the Korean Peninsula.

What is SLUB?

SLUB is a previously unknown malware that used a watering hole (a compromised website that targets are likely to visit) to spread. The website was compromised by exploiting CVE-2018-8174, a VBScript engine vulnerability that allows for Remote Code Execution (RCE) — patched by Microsoft in May 2018. After a target visited the website, the SLUB loader was downloaded to the victim’s machine, which then ran a hidden PowerShell window to download the SLUB backdoor. This process exploited a Local Privilege Escalation vulnerability (CVE-2015-1701) — patched by Microsoft in 2017 — whereby the data from the System token is copied into the token of the current process allowing a local user to execute the payload with System process privileges. The SLUB downloader also checked if antivirus processes were running, and if so, exited without doing anything.

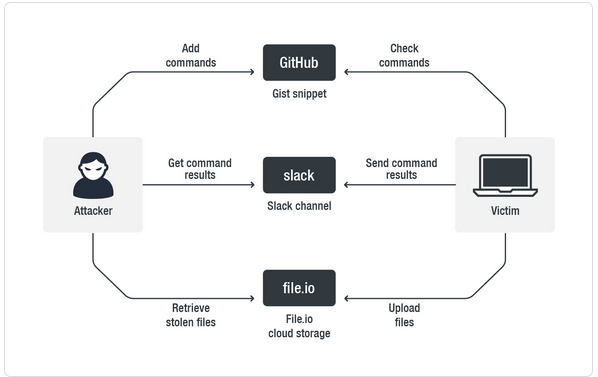

The SLUB downloader also modified registry keys on the infected system to maintain persistence, and the SLUB backdoor received commands from GitHub, sent the output of those commands to a private workspace in Slack, and uploaded data to file.io for exfiltration by the malware’s operators. The process is depicted below.

The SLUB backdoor supports a number of commands and subcommands to initiate processes, enumerate file systems, modify registry keys, and delete the malware from disk. Trend Micro assessed that the GitHub account and Slack workspace were created for this campaign on 19 and 20 February and the malware itself was compiled on 22 February. The threat actors then tested the malware on 23 and 24 February before infecting the first victims on 27 February.

New Version of SLUB

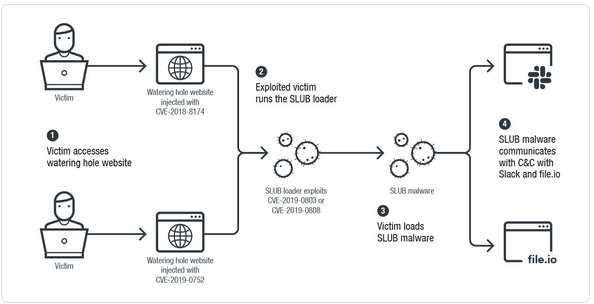

After Trend Micro published their research on SLUB in March, a new version was discovered on 9 July that was delivered via a different watering hole website. This website was compromised using the CVE-2019-0752 vulnerability — an Internet Explorer vulnerability that allows for RCE — which was patched in April. This version of SLUB stopped using GitHub to supply commands and instead relied heavily on Slack for all communications.

This version of SLUB also exploited Local Privilege Escalation vulnerabilities (CVE-2018-0808 and CVE-2019-0803) that were patched in March and April respectively. Like the previous version, exploits, the loader, and the SLUB malware were hosted on the compromised website and C2 communications utilized private workspaces within Slack, while file.io was used for data exfiltration.

Rather than using GitHub to issue commands, this version pinned messages into the Slack channels corresponding to the infected machines. The Slack workspace for this campaign was active since May, indicating that the threat actor was modifying tactics to continue reconnaissance activities.

Connection to the Korean Peninsula

The previous Trend Micro analysis only indicated that the watering hole website “can be considered interesting for those who follow political activities.” The 16 July report provides more information, revealing that both websites “are supportive of the North Korean government.” Moreover, the SLUB malware was observed enumerating KakaoTalk directories, collecting Hangul Word Processor (HWP) files, and exfiltrating this data to file.io. SLUB also used two Slack teams (sales-yww9809 and marketing-pwx7789), which each contained one user with a GMT timezone set and one user with a KST timezone set.

- sales-yww9809

- Lomin (lomio8158@cumallover[.]me; created 23 May 2019; GMT Africa/Monrovia)

- Yolo (yolo1617@cumallover[.]me; created 23 May 2019; KST Asia/Seoul)

- marketing-pwx7789

- Boshe (boshe3143@firemail[.]cc; created 17 April 2019; GMT Africa/Monrovia)

- Forth (misforth87u@cock[.]lu; created 17 April 2019; KST Asia/Seoul)

As mentioned above, the lack of operator-owned infrastructure restricts open-source researchers from identifying the threat actors. However, Slack has been notified of the activities and a forensic investigation is likely in progress. The evidence does indicate that these threat actors were targeting individuals with an interest in the DPRK and the mission was to collect Twitter, Skype, Kakao and other communications data along with HWP documents. DPRK researchers often visit DPRK-owned websites, though the threat actors could have been targeting those sympathetic to the DPRK as well. At this point, we do not have enough information available to determine the political motivations of the threat actors. However, DPRK threat actors have targeted academics focused on DPRK research at the end of last year.

Conclusion

This malware family was distributed via compromised websites, which researchers have no control over. Thus, researchers should assume that any primary source DPRK website contains scripts that attempt to execute remote code on their systems. Researchers should ensure that their versions of Windows are updated (migrate from Windows 7 to Windows 10 if you haven’t already) and that their IE browsers are updated as well. Also, researchers should be using an anti-virus solution with updated signatures. Moreover, researchers should consider deploying an Intrusion Detection System to gain visibility on the packets that are traversing their networks (especially when conducting research outside of their enterprise environments). Researchers should also utilize encryption for email and word processor documents, especially if these documents contain sensitive information. Finally, consider using multiple devices and not storing personal data on a system used for DPRK research.